AI: Do we need a big law to govern it?

Vision Assessment of the EU Intelligence Act

Vision paper written as elaboration of Francesco Grillo's column (for the Italian newspapers Il Messaggero and Il Gazzettino).

Does it make sense to attempt to govern technological development like Artificial Intelligence (AI) through law? What intellectual tools do we need to understand a phenomenon that is changing the way we – humans – transform information into knowledge? These are considerations we are no longer accustomed to, and they should form the basis of judgment on the massive effort that European institutions have made to make Europe the first continent to have a law (recently approved by the European Parliament) on AI.

Technological progress is indeed characterized by two families of inventions with completely different impacts. Some - much more numerous - have a specific purpose (such as the washing machine, which nonetheless has had enormous merits). Others have theoretically infinite uses (like the discovery of fire during the Neolithic era). AI is the twenty-fifth in the history of "general-purpose technologies" (GPT) according to the classification of Oxford University Press. It resembles more closely the invention of tools that allowed writing (papyrus, 5000 years ago in Egypt); Gutenberg's printing press (which heralded the end of the Middle Ages). The extraordinary characteristic of these types of technologies is that they change all human activities. Furthermore, AI is poised to change our very cognitive processes. For all GPTs, and even more so for AI, the difficulty lies in attempting to govern a process with unpredictable outcomes.

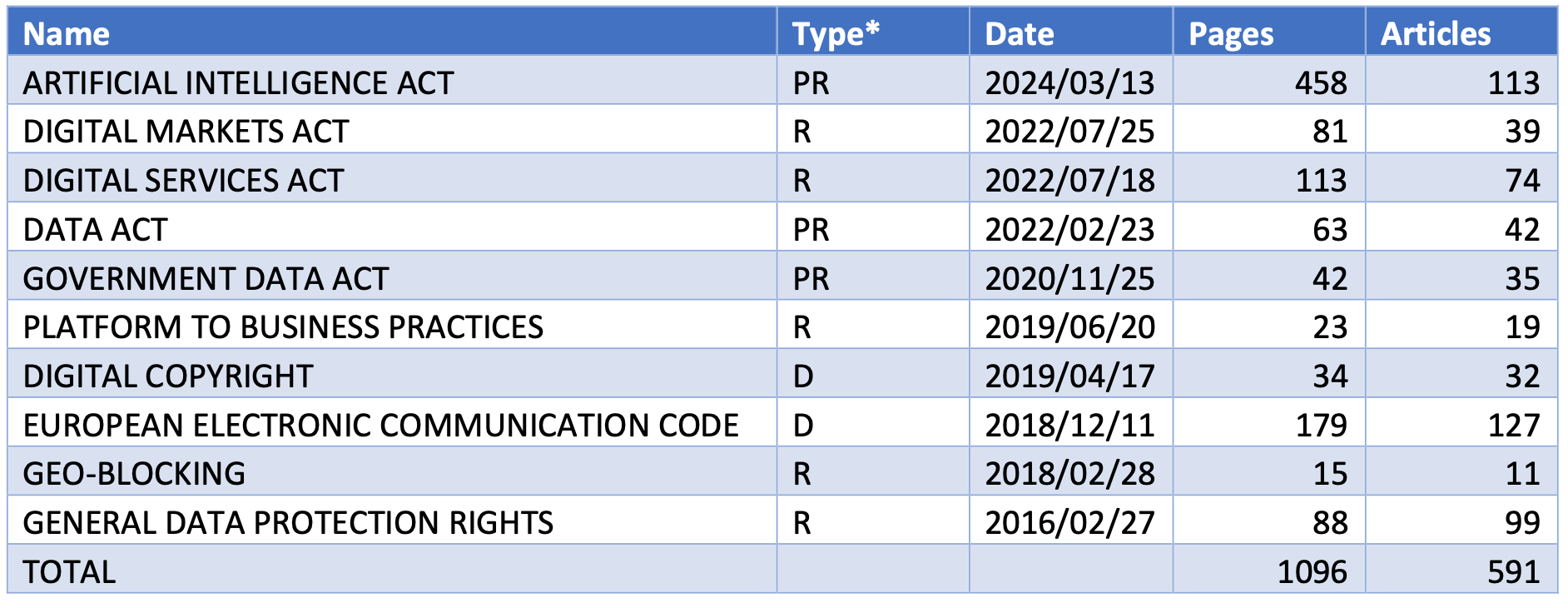

These philosophical and quite concrete considerations seem to have been overlooked by the legislators of the European Parliament. The first surprising thing is the magnitude of the effort. The proposed regulation on AI consists of 458 pages articulated in 180 recitals, 113 articles, and 13 annexes (Table 1). This is a sizeable increase compared to previous versions of the act and adds to nine other directives and regulations produced by the Union on digital issues in the last eight years. However, this regulatory binge seems to be the conditioned reflex of a legislator who, feeling surpassed by the phenomenon on which to intervene, tries to chase its manifestations that meanwhile multiply.

TABLE 1 MAIN EU LEGISLATIVE ACTS (SINCE 2016)

SOURCE: EUROPEAN COMMISSION AND EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

* Type: we here distinguish between Directives which need to be transposed into national laws; regulations issued by the European Parliament and the Council which are immediately applicable; and proposal of regulation of the European Commission for a regulation of the European Parliament and the Council.

**Author: EC = The European Commission; EP + EC = The European Parliament and the Council

When the Commission submitted the first draft of the AI regulation to the Parliament and the Council in April 2021, the world was living in a different technological era. The latest generation of the Covid19 vaccine had not yet been approved, and Facebook had not yet changed its name to Metaverse. No one imagined that a foundation created by Microsoft (OPENAI) would introduce an AI model capable of reaching 100 million users in just two months, a year and a half later (breaking all previous records). The world has outpaced institutions, and entrusting the response solely to jurists produces a number of paradoxes.

It may be a mistake (tragically comedic in Italy) to have decided, for example, to classify even just supporting the judiciary in researching and interpreting facts using AI as "high-risk." Even deciding to begin the regulation by banning the use of systems that evaluate the social behavior of groups of people could deprive us of a tool we may soon need to counter environmental disasters. But each of the norms of such a vast instrument structurally lends itself to missing opportunities (especially in research compared to processes that risk excluding us). Moreover, it does not prevent the dangers of uncontrolled innovations from hitting us from countries that are advancing with less scrupulous experiments. What is a potentially different approach?

One was attempted some time ago by the British, who, precisely on digital matters, may have the advantage of not having to adhere to the European method. The idea is to intervene with an authority (called CBI in London, and is the equivalent of our ANTITRUST) that adds to its competences not so much the regulation of a technological process of "general application" that is not regulatable, but rather the study of the impacts of those technologies on industrial sectors (and public services). Pools of doctors, biologists, and computer scientists could, for example, focus on identifying risks and opportunities for healthcare and research on new drugs. The same would apply to schools, where the effects of technologies vary by subject and age of students/teachers. The office for AI envisaged by the new law would be rearticulated in this way (avoiding the epistemological error of continuing to delude ourselves that there are really "experts in AI", whereas this technological wave forces us to seek entirely new lenses).

But the saga of the AI regulation also reveals a conception of consensus that is rather strange. It seems that the timing and contents of the act approved last week were greatly conditioned by the political will to close a deal (which, instead, remains open) before the next elections. This is a strange conception because it is difficult to imagine that even the vote of the relatives of European parliamentarians could have been swayed by being able to say they were the "first" to have an AI law in the world.

In reality, part of the problem we need to solve is that - among so many redundant technicalities - there are no more than a couple of thousand European citizens who are aware that the future of mankind is at stake because of these issues. Our future should become a political and moral issue. Instead, currently it is the territory of "experts" who, by definition, cannot imagine what is not yet there; and of lawyers or lobbyists whose profession maintains the status quo; and of Commission officials who should have no interest in seeking "consensus".

This article is a Vision Think Tank paper written by Francesco Grillo and Radi Damianov.