The future of the Stability and Growth Pact

Merits and limits of the Commission's proposal and an alternative approach.

Vision Think Tank1 - March 2023

The Stability and Growth Pact is everywhere, but not in economics statistics. We can rephrase the Nobel Prize Robert Solow to express the paradox of probably one of the most contradictory regulations adopted by the European Union. Before it was suspended in 2020 to deal with the pandemic, the Pact got to be criticized by both the States worried about stability – the Nordic ones – and those in great need of growth (as Italy and Spain). Two months ago, the European Commission proposed a revision of the pact, which has both merits and limitations that are worth discussing to improve one of the cornerstones of European Integration.

But what is the Pact?

The Pact is a set of rules aimed at ensuring that Member States pursue sound public finances and coordinate their fiscal policies, to enforce the deficit and debt limits established by the Maastricht Treaty. The fiscal discipline is ensured by the Pact by imposing each Member State limits on government deficit (3% of GDP) and debt (60% of GDP).

Those who easily speak of the failure of the EU economic governance system, adopted in 1997 and last reformed in 2013, are wrong. The creation – never tested before in history – of a monetary union among sovereign states in 1999 created the risk of a weak incentive among less rigorous countries to control their finances. The Pact had the merit of preventing even worse troubles than those experienced with Greece in 2011.

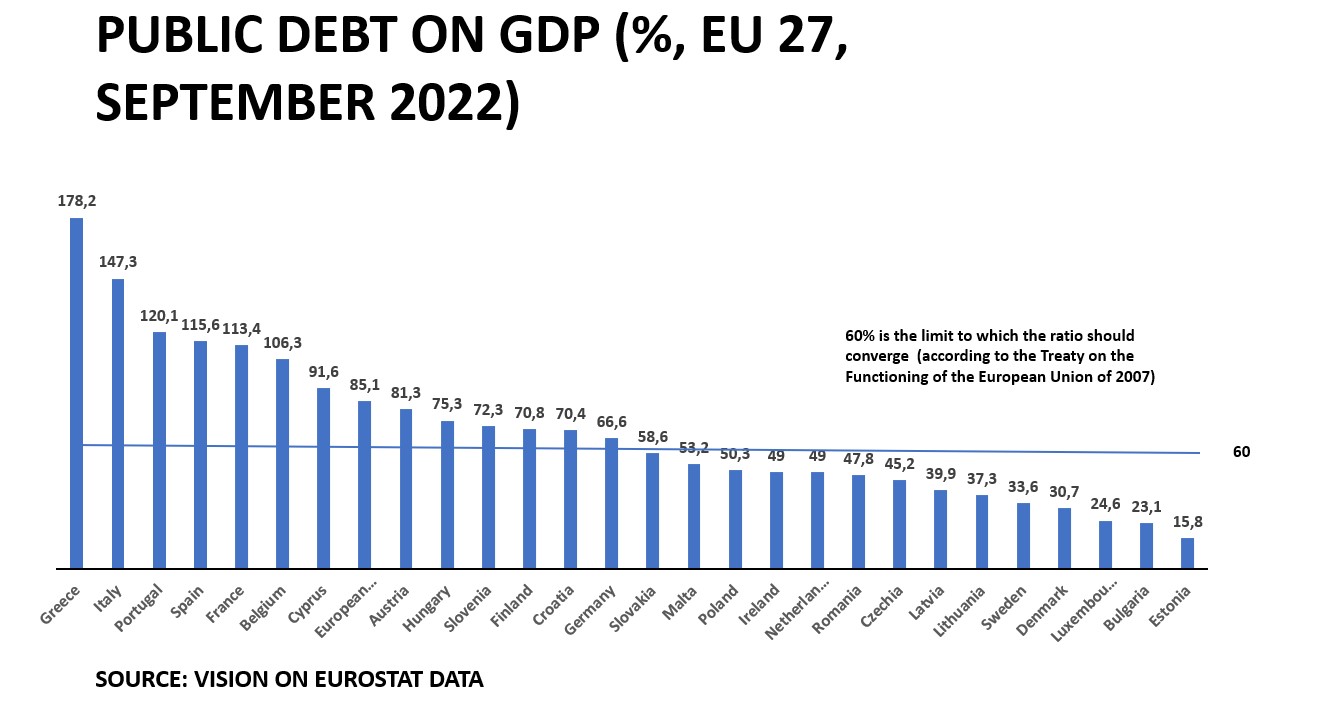

And yet, if we look at the statistics, the critics seem to be right. Referring to the years before the pandemic- that led the finance of all countries to explode - as many as 13 out of the 28 EU countries still had public debt to GDP ratios higher than the 60% limit set by the Treaties – with higher debt levels within the Euro area than outside. At the same time, the growth of the Euro area itself (2% between 2014 and 2019) continued to be structurally lower than that of the major economies (3% in the Us; over 6% in China and India).

The existing EU framework establishes similar adjustment efforts, although Member States have lots of differences about of their debt position and fiscal risks. Some States have a very high debt exceeding 90% of GDP (Greece and Italy the worste countries). 14 States have a debt lower than the 60% limit, while many are in an intermediate situation.

The Commission's proposal

The 9th of November, the Commission made a new proposal which has already become partially operational with the guidelines announced yesterday - 8th March - by Commissioners Gentiloni and Dombrovskis. The Member States will have to follow the guidelines for the next year.

The 3% rule on the deficit remains unchanged and applies to everyone; moreover, if violated, the excessive deficit procedure continues to apply.

The proposal formulates a new fiscal coordination process divided into four phases. Countries are divided into three groups with high, medium and low vulnerability on debt, using a consolidated analysis method. More specifically, the ex-ante division is based on the debt/GDP ratio: less than 60%, between 60 and 90% and higher than 90% with differentiated rules for each group.

Secondly, the Commission defines a path to recovery that, compared to the current mechanism, does not use the deficit but public spending as an indicator (in order to exclude the effect of higher taxes, but also the charges automatically applied in the event of a crisis).

Eventually, each country proposes a plan of reforms and investments (as for the Recovery and Resilience Plan) that can raise the growth or reduce debt in the medium term, with a slower adjustment path. In particular, countries with a debt exceeding 60%, propose their own multi-year plan to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Finally, the Commission evaluates the proposal, reporting to the European Council, and, once it is approved, each State implements it. Each country thus takes a political commitment to carry out the plan before its partners.

Independent fiscal institutions established in each EU State will monitor the compliance with the national medium term fiscal-structurals plans, providing backing for national governments. Independent fiscal institutions will have a role in providing an ex-ante assessment judging the adequacy of the plans and their forecasts. This would be helpful for national governments in the design phase. In addition, independent fiscal institutions could strengthen enforcement at the national level by evaluating compliance with the agreed multiannual net primary expenditure path in retrospect, as well as assessing the validity of explanations for any deviations from the path. While the Commission and the Council, responsible for EU surveillance, could consider the evaluation of independent fiscal institutions, they would ultimately retain the authority to propose and adopt the final decision.

The mechanism, welcomed as radical by some, is actually a development of the approach in place since 2013. The indicator that controls finances becomes public spending, whereas it used to be the “medium-term deficit”, as in the reform proposal, that differentiated countries based on debt sustainability. Even the old Stability and Growth Pact provided trajectories to be achieved over time, although now they are extended up to 10 years. The real novelty, however, is the introduction of reforms and investments as a lever to make the adjustment less burdensome. However, there is a conceptual as well as a political problem on the issue of reforms.

An alternative approach

It is absolutely true that, by reforming (and reorganizing) the machinery of the State, it is possible to restore balance. But is equally true that it is risky for the Commission to evaluate, based on what is considered to be "good governance", the programs of national governments. This is a serious misunderstanding, because the reality is that we and the Commission are navigating complexity (“uncharted waters”, as Draghi would say), made new by great technological discontinuities. There is no longer a handbook of the “good reformer” to follow. And there is no moment of “negotiation” of a package of changes to be followed by an “implementation”.

It is much better to further simplify, by agreeing with individual states (and the entire Council) a few objectives that everyone can understand, so that those objectives become political. If there was a Union fiscal tool capable of automatically supporting those in difficulty in times of crisis, it would be good for public spending, but also for public debt reduction. With regards to such objectives, discretion should be left to the States to follow their own approach. This would also increase the possibility of learning from each other and the Commission’s task should be to organize such learning process.

It may not please those who, from a supranational public administration, have the urgency to quickly make national public administrations do things. And yet, the great problem of the twenty-first century is governing an economy in an era defined by risk. The challenge to be pragmatically won is to ensure enough “stability” for citizens, while we try to grow by adapting to a context that requires completely new tools.

------------

1: The co-authors of this paper are Giorgia Caianiello and Francesco Grillo from Vision Think Tank. The paper is based on Francesco Grillo's column for the Italian newspaper il Messaggero, il Mattino and Gazzettino del Nord-Est.