Real Problems and Wrong Tools

The European Strategy on Greenwashing.

Vision Paper by Francesco Grillo, Valerio Rosa and Silvia Scarafoni.

Elaboration of an article originally published in Il Messaggero by Francesco Grillo.

The problems are real. The goals are valid. But the tools, almost always, follow the same pattern: laws that are difficult to interpret, whose violations result in fines intended to curb harmful behavior. This seems to be the approach that has shaped the most recent generation of European environmental policies (a similar method was also applied in attempts to defuse threats posed by digital platforms).

It’s a method that—within just five years—has managed to turn the flagship policy of Ursula von der Leyen’s first Commission into the area of greatest strain in her second term. So much so that it is over yet another regulation—the directive intended to target the misuse of sustainability as a marketing weapon by companies—that the Commission President risks losing the confidence of her parliamentary majority.

No one in Europe (unlike in the United States) seems to deny that controlling climate change is among the top priorities. And nowadays, we no longer even need science to notice the phenomenon: a simple thermometer is enough to show that—year after year, almost every day, every hour, and in nearly every city—we are reaching the highest temperatures recorded since the 1970s.

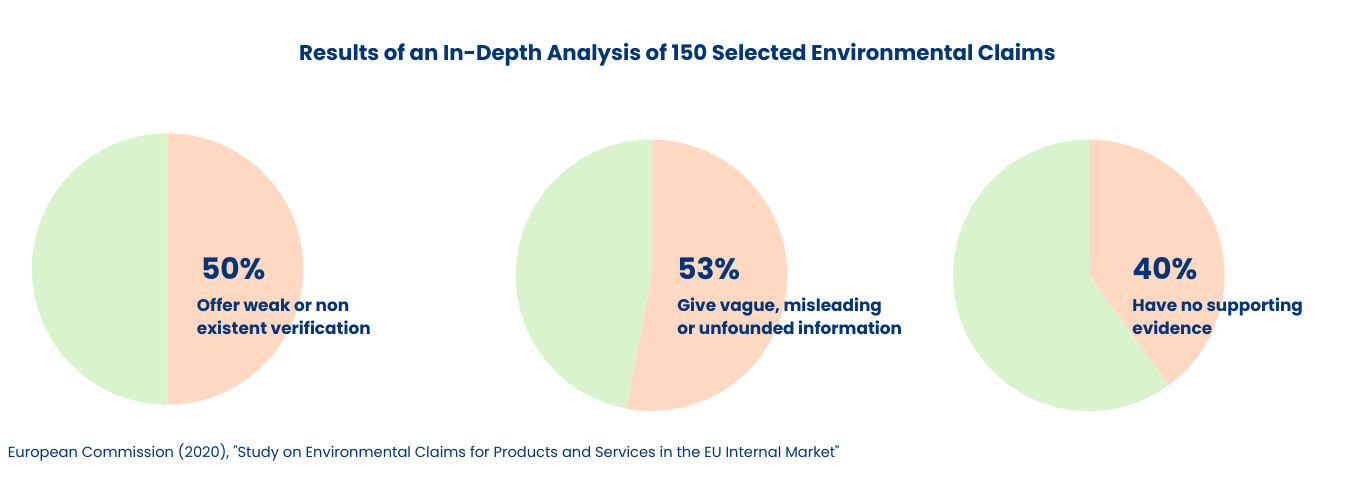

Against this backdrop, the European Commission has been focusing on a problem within the problem: the widespread corporate habit of announcing decarbonization goals which, according to the Commission itself, are false in half of all cases. This is not merely a political observation—it is backed by EU-wide legal analysis. A 2020 Commission‑mandated study evaluated 150 real environmental claims.

As the infographic below shows, over 50% of those claims were found to be vague, inaccurate, or unsubstantiated.

This practice is doubly damaging: consumers are misled and continue to be exposed to pollution, while honest companies are undermined by deceptive advertising. To address this, the Commission proposed a directive a year ago requiring all companies that claim their products or activities have a positive environmental impact—or are working to reduce a negative one—to substantiate those claims with scientific evidence. This proof must be verified by Commission-appointed professionals. And all of this must occur before the claim reaches consumers. Penalties for violating these obligations can reach up to 4% of a company’s total turnover.

The directive’s push for companies to reflect seriously on their strategies is commendable. But the law also risks being, as usual, “too narrow” to catch the most harmful behaviors, and “too broad” in a way that could stifle innovation. The directive, in fact, raises a number of questions: does it include cases where no claims are made but companies simply give their brands a green makeover? Or those who rebrand entirely—like BP, which renamed itself "Beyond Petroleum" after a catastrophic oil spill? And how do we "certify" the sustainability of a startup engaged in uncertain but potentially significant research?

The truth is that the European Union (ironically accused by some of being “laissez-faire”) keeps repeating the same two mistakes. It starts from the idea that “consumers” must be protected (an attitude more typical of 19th-century states). And worse, it assumes that reality is black or white—and therefore certifiable. But in reality, the assessments a serious business makes are always shades of gray. They involve difficult trade-offs (such as between disposing of wind turbine blades and the renewable energy they produce). And risks that a system of penalties may not be able to capture.

But it’s not for these reasons that the Commission suddenly reversed course and withdrew the proposal a few days ago. The actual cause lies in a never-ending tug-of-war between conservatives and socialists, played out over semantics (the very words the directive aimed to reclaim) rather than strategy.

There is a way to save the objective without discarding it along with the tool. We should truly harness the power of consumers and savers as mature citizens. We should correct what is essentially a "market failure" by encouraging the creation of agencies that can provide individuals with concise and reliable information on the sustainability of companies and products. Ultimately, the work of professionals at this level should be funded by the very citizens who demand quality information in order to make informed choices. But at the outset, the European Union itself could provide incentives—together with institutional investors who have a stake in greater transparency.

After all, many environmental policy failures (such as the corporate sustainability reporting directive, and the broader market for buying “pollution rights” to fund sustainable projects) stem from flawed measurement tools and the lack of independence among those doing the measuring (from audit firms to rating agencies).

Making citizens the clients of quality information—who can buy it, but also sell it—is an ambitious but not impossible path of innovation: after all, in its early days, Moody’s survived thanks to subscriptions from individual savers for its publications.

The Europe of the future must find its own path to face the challenges that are dragging us out of history. To succeed, we must come up with radically new frameworks—ones that rely entirely on citizens who can defend themselves not with fines, but with their own choices. This is the only way to restore meaning to words like "resilience" and "sustainability"—words that, in the beginning, were right.

References:

European Commission (2025). Green Deal. Link.

The Economist (2024). How to pay for the poor world to go green. Link.

The Guardian (2025). EU rollback on environmental policy is gaining momentum, warn campaigners. Link.

The Guardian (2025). Political cowardice hindering Europe’s climate efforts, says EU’s green chief. Link.