Beyond Overinvestment in Large Language Models

Three mega opportunities for Europe

Article by Vision Team

"There is a saying: ‘The United States invents, China copies, and Europe regulates.’ The origin of this statement, which has circulated for years within American universities, remains unclear. However, it captures only a fragment of the vast technological trends that will shape the future—far more significantly than the geopolitical factors that dominate talk shows. In the realm of research on artificial intelligence (AI)—which enables a robot capable of analyzing vast amounts of information to provide a response—Europe has clearly missed the boat. Nevertheless, we might find at least three more opportunities, by adopting a strategy similar to China's in the first decade of this century: using foreign inventions as leverage to transform an entire society. This should be the starting point for the industrial policy that everyone is discussing, which has found a capable champion in Teresa Ribera, the European Commissioner from Spain’s socialist government.

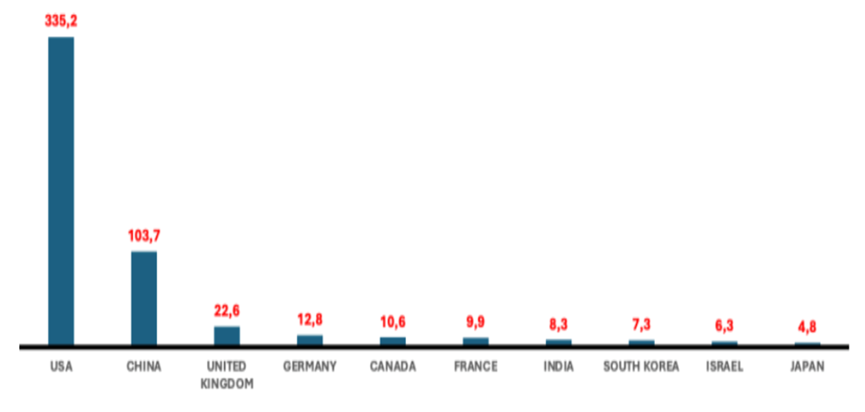

PRIVATE INVESTMENT IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE BY GEOGRAPHIC AREA (2013-2023, BILLION USD)

SOURCE: Vision on Standard University Data

The Draghi Report highlights the $800 billion annual investment gap Europe must close to avoid a "prolonged decline". Yet, even more striking is the discrepancy between Europe and its main competitors in specific sectors.

In AI investments, the United States has spent nearly $350 billion on research over the last decade—three times more than China, which in turn has invested three times more than all 27 EU countries combined. These disparities manifest in intellectual property that will be difficult to replicate: Alphabet alone boasts 20 "large language models" (the foundation of AI), whereas all European companies combined possess only 2.

In this context, chasing the Americans is a task only the Chinese—due to their scale, interest, and talent—are capable of pursuing. What can Europe do then? In fact, as The Economist recently warned, being the first to innovate may not suffice this time, for two key reasons.

First, the problem with the AI models launched by Silicon Valley in the past two years is their excessive breadth. These models provide answers by incorporating all available information from the web, rendering responses insufficiently precise—especially in applications like medical diagnostics or autonomous driving. To address this issue, the quality of each piece of information (which is relative to its intended use) must be evaluated through time-consuming statistical computations. This drastically increases the training costs for the AI systems and the energy consumed to answer even a single question.

Secondly, AI remains a "solution in search of a problem." While the famed Californian programmers excel at their craft, they have thus far monetized their talent mainly through advertising revenues. AI holds the potential to revolutionize fields like healthcare and education—countering those in Europe, for example, who view machines solely as a threat of alienation. Yet, in Palo Alto, they have little understanding on how industries and public services work, which, for the most part, remain the same as those we used to work in before the first email was ever sent.

Here lies three significant opportunities for Europe.

First, Europe could build on available technology to create more specialized AI models, such as systems tailored to address the inefficiencies of Italy’s legal system or to more accurately forecast the medium-term consequences of climate change and recommend appropriate solutions.

Second, Europe could leverage AI to boost productivity in traditional industries, such as agrifood, which could benefit from more precise techniques, or even in defense, where technology must radically transform itself by observing how to change the conflicts in Ukraine and Lebanon.

Lastly, Europe could capitalize on its experience to restructure the delivery of public goods (from housing to mobility) using digital technologies, where it might act ahead of others. However, this will require not only new skills and regulatory frameworks, but also substantial investment, which, though, is politically costly. As for competency, we no longer even have to refer to strictly technical ones; Europe requires entrepreneurs who can reimagine how technology can revolutionize their industries, and the pragmatism to guide such transformations. Today, there seems to be a passive management within major companies, with dominant positions slowly eroding, while smaller enterprises appear resigned to merely settling for niche markets.

As discussed during the 5th Siena Conference on the Europe of the Future, it is necessary, then, to have the courage to combine the (excessive) regulation of digital with the deregulation of sectors that are still protected today. Selectively exposing European companies to competition that is also curbed in the U.S. and China may foster the new industry leaders, better than billions of investments.

Many were surprised when Ursula von der Leyen assigned both the energy transition and competition portfolios to the same commissioner, Teresa Ribera. However, it is Ribera—Spain’s Deputy Prime Minister—who has the opportunity to generate the idea of equipping Europe with a genuine industrial policy by uniting the two levers.

References:

European Commission (2024). The future of European competitiveness. Link.

The Economist (2024). The breakthrough AI needs. Link.