Science: Chinese rise and European decline...

...three ideas for going back to the future

Paper by Vision, editors Greta Aurora Zottoli and Valerio Rosa.

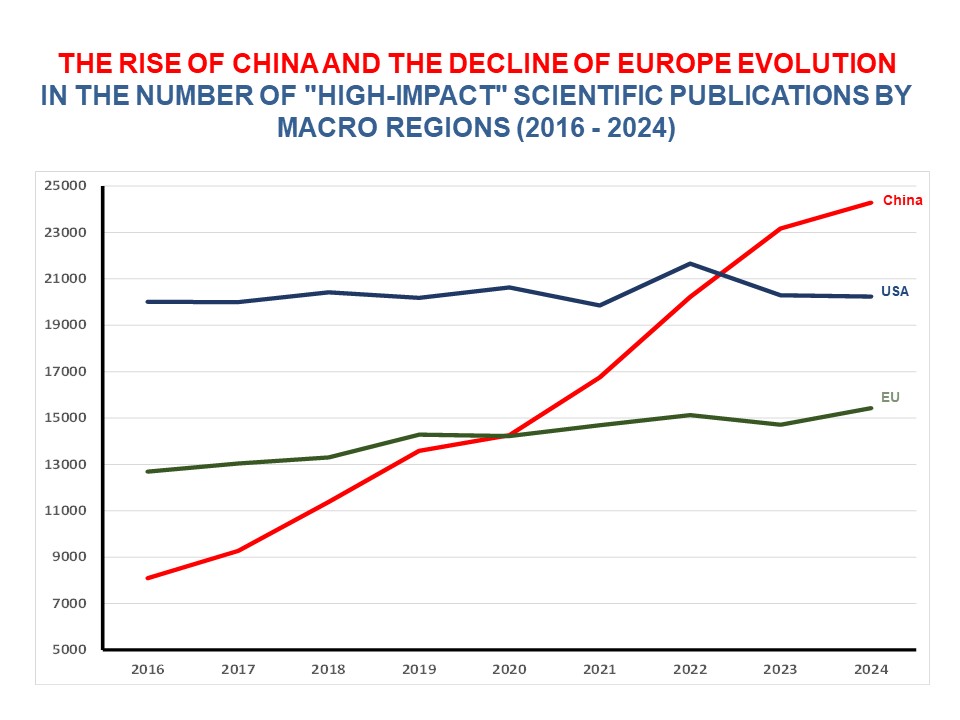

Last week cover story in The Economist delved into a story that precedes many geopolitical considerations, which often do little to shift the balance of power. As highlighted by the accompanying graph, China has just surpassed the United States in the number of high-impact scientific publications, marking the culmination of a pursuit that began at the start of the century. However, this news contains another element that concerns us more closely: the European Union seems to be falling out of the competition that will most define the new world order. This should be one of the top priorities on a new European agenda, which cannot rely on past glories to secure its future.

Source: Vision based on data from The Economist and Nature

China is, however, just coming back. The Middle Kingdom once brought inventions to Europe that changed the course of history: the compass, gunpowder, and printing. Until the Renaissance, China (alongside India) was the world’s largest economic power, followed distantly by a fragmented Italy. Just 20 years ago, the United States produced 20 times more research than China; by 2013, it was only four times more. At the end of 2023, according to Nature (one of the world’s two most credible scientific journals), China had overtaken the US. Yet, alongside China’s rapid rise, we see a slower decline in Europe. Among the top 50 universities for scientific output, only six are European. Of these, two are in the United Kingdom and one in Switzerland, leaving just three within the EU: two in Germany (which still boasts the prestigious Max Planck Society, alma mater to Albert Einstein and Werner Heisenberg) and one in France. The continent that once led the world in innovation now seems content to reminisce about its past.

Clearly, all rankings have their limitations. Those that calculate scientific supremacy by counting citations of scientific papers face issues of “citation cartels.” The global scientific community has long fragmented into hundreds of small groups (in Italy, this corresponds to 190 scientific-disciplinary sectors guiding the careers of 40,000 lecturers) where researchers cite each other to advance their careers. Nature’s numbers, for example, suggest that Chinese scientists are twice as likely to cite each other compared to their German counterparts. However, concrete research outcomes also indicate that Europe is struggling: most companies experimenting with "flying cars" that could revolutionize urban mobility are Chinese; most firms attempting to transition AI models from computers to actual androids are American. These represent different research models – American and Chinese – but Europe appears sidelined. Exceptions like France’s MISTRAL, which aims at non-proprietary AI models, are conceived and promoted at the national rather than the EU level.

Innovation, rather than geopolitics, will determine the “wealth of nations” and the future world order. Therefore, fostering innovation should be a top priority for Europe, which cannot continue the self-congratulatory practices of the past five years without concrete results.

A strategy to revitalize Europe must leverage three key areas. More efficient regulation: Regulations are essential, especially as human rights are at stake, but we cannot allow them to become oceans of confusing requirements that ultimately harm the very subjects (individuals, small businesses) we aim to protect. Redesign of research programs (like Horizon): A European industrial policy should aim to select and nurture “champions” capable of competing with Chinese and American giants. Meanwhile, the extensive research program managed by the European Commission (HORIZON) must be restructured around concrete problems each project aims to solve, as attempted by Italian economist Mariana Mazzucato. Interdisciplinarity: Europe should restructure its research around interdisciplinarity, moving away from the logic of “experts” who manage issues without solving complex problems. This approach echoes the “universal intellectuals” (like Enrico Fermi and Guglielmo Marconi) who were driven by the impact their work could have on contemporary life, laying the scientific foundations for progress now waning.

Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico observed that civilizations experience cycles of expansion and decline. Like China, Europe can find in its tradition the key to modernity. However, this requires the humility to acknowledge that certain advantages have been exhausted and the ambition to chart a new path toward the future.

References:

The Economist. (2023). "China has become a scientific superpower: From plant biology to superconductor physics, the country is at the cutting edge." Link

Nature. (2023). "China overtakes United States on contribution to research in Nature Index." Link

Science. (2023). "China overtakes US in contributions to nature and science journals." Link

Beeson, M., & Li, F. (2023). "China's Place in Regional and Global Governance: A New World Comes Into View." Link

The Guardian. (2023). "Why Europe is a laggard in tech: The continent is facing a sector-specific problem that will spread if reform is not forthcoming." Link