Europe is... what you eat

The (radical) reform of the common agricultural policy as a decisive issue in the next European elections.

Vision paper written as elaboration of Francesco Grillo's column for Il Messaggero.

"In this room there is no one whose family tree doesn't reach back, sooner or later, to farming roots", with these words, the first President of the European Commission, Hallstein from Germany, presented the first budget of what was then called the European Economic Community (EEC), dedicating 75% of its resources to agriculture. Seventy years later, Europe is returning to the land because there is no other productive sector that will have a more direct influence on the next election of the European Parliament. We are facing one of the most critical battles in the history of all generations. Both the past and the future of the Union seem tied to food, which is why it is in the interest of all political parties to better understand the triple paradox in which farmers and large food processing industries are trapped.

Less than 5% of European workers are engaged in agriculture, living with a triple contradiction that makes them politically significant. Firstly, agriculture manages to be both the sector that (after energy) contributes the most to climate change and is simultaneously the one that suffers the most devastating consequences. It is worth noting that the progressive increase in awareness of the importance of food culture has been paralleled by a growing impact that this sector has had on climate change. However, this data varies by production: meat production generates more emissions than the entire chemical and petrochemical industry, while oil and rice are at high risk.

Secondly, agriculture is still the industry to which the European Union dedicates the most resources (€60 million annually) and yet, it has also sparked the harshest protests.

Finally, there is no doubt that food is the distinctive value that everyone recognizes in Europe, yet this struggle fails to translate into added value. For example, Italy continues to export less than it imports. The tractor protests reaching Brussels are proving to be one of the few factors capable of truly shifting votes and changing European priorities. Giorgia Meloni, the Italian Prime Minister who added the mandate of "food sovereignty" to the Ministry led by Francesco Lollobrigida, immediately understood the need to increase efforts to protect farmers from uncontrollable changes. However, can we imagine a reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) radical enough to move from "defending" a sector that needs support, to a strategy that transforms it into an industry capable of triggering major innovation processes? There are three ideas to further develop.

Firstly, we must abandon the logic that has accompanied the CAP for seventy years of permanent subsidy. This subsidy, strangely enough, is linked to the quantity (hectares) of cultivated land. It's a mindset that assumes the inevitability of decline and doesn't reward those who - through intelligent use of technologies or better organization - increase production per hectare or the value they extract from that production. Over time, subsidy payments have been conditioned by a series of controls, not always shared, which have had the damaging effect of increasing bureaucracy that ultimately harms those with less time. However, the idea of "income guarantee" (as explicitly provided by the largest of the two CAP "funds") discourages (just like the Italian "citizens' income") those who want to try be independent of state support. One hypothesis could be to help those who have achieved less success and want to do more.

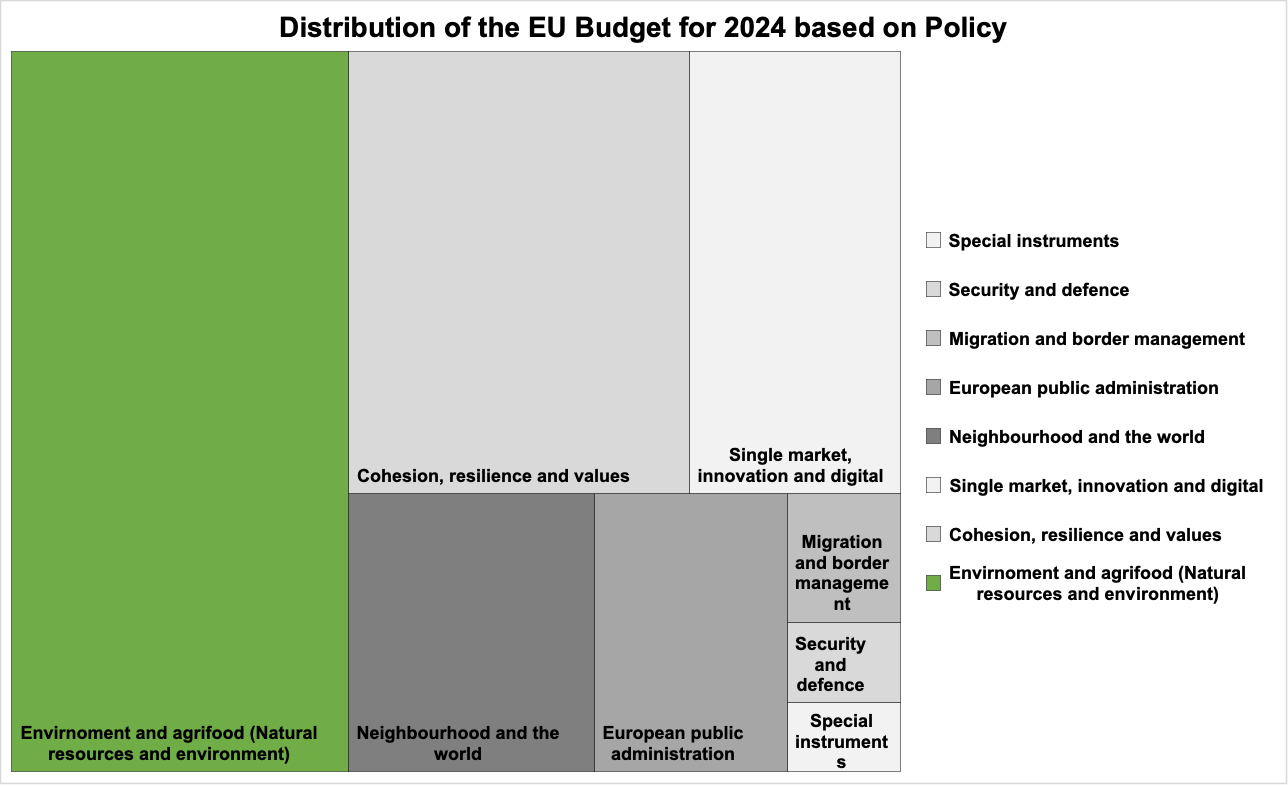

Figure 1 EU annual budget distribution by categories (2021-2027, billions of Euro)

Secondly, we must abandon the romantic but harmful idea of protecting small family businesses, there exist mechanisms for redistribution that keep the small ones alive. Instead, it must be admitted that agriculture is an industry. Like all others, it needs economies of scale and specialists who, within the company, specialize in finding new technologies or markets. An alternative to the large companies that dominate international markets (such as the American or Brazilian ones) has been cooperatives, which have even managed to organize sophisticated distribution channels.

Thirdly, we must strengthen the second pillar of the CAP, the fund for rural development, and this fund must host territorial strategies aimed at making entire territories both more competitive and less environmentally impactful. Currently, the logic of the "green deal" that Europe has imposed on itself imposes a series of prohibitions and requests for land not to be cultivated on farmers: it is wrong for these measures to be the same for everyone, in a continent ranging from the lands of Santa Claus to those hot lands bordering Morocco. Much more respectful of the intelligence of businesses, which should be treated as such, can instead be the setting of a few clear objectives that are compatible with the economic and environmental sustainability of the sector. A few "targets" should be defined with businesses and institutions in a certain area (the Italian provinces were perhaps the right size) on which to depend (just like for the National Recovery and Resilience Plan) the provision of funds that accompany the ambitious transformation that Europe must undertake as its mission.

Agriculture has so far been the most faithful mirror of a trait that has defined Europe: an endless negotiation to pull on one side - the large industrial enterprises like Germany and Northern Europe - or on the other - France with Italy and Spain - a blanket too short. We have been in a century for some time now that asks us to abandon stereotypes long dead and realize that in agriculture (as well as in tourism), there are opportunities to conquer leadership in a century that began twenty-four years ago.

This article is a Vision Think Tank paper written by Francesco Grillo and Radi Damianov.

References:

Common agricultural policy, (2024). Agriculture and rural development. Available at: Link.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Budget, (2021). The EU’s 2021-2027 long-term budget and NextGenerationEU : facts and figures, Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2761/808559

Grilllo, F. (2023). Climate fatigue isn’t a sign that Europeans are in denial – it’s a sign of their fear. The Guardian News and Media. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/nov/08/climate-fatigue-europe-voters-green-costs

Ritchie, H. (2020). “Sector by sector: where do global greenhouse gas emissions come from?” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/ghg-emissions-by-sector